I’ve read and been thinking about Underwood and Sellers 2015, How Quickly Do Literary Standards Change?, both the blog post and the working paper. I’ve got a good many thoughts about their work and its relation to the superficially quite different work that Matt Jockers did on influence in chapter nine of Macroanalysis. I am, however, somewhat reluctant to embark on what might become another series of long-form posts, which I’m likely to need in order to sort out the intuitions and half-thoughts that are buzzing about in my mind.

What to do?

I figure that at the least I can just get it out there, quick and crude, without a lot of explanation. Think of it as a mark in the sand. More detailed explanations and explorations can come later.

19th Century Literary Culture has a Direction

My central thought is this: Both Jockers on influence and Underwood and Sellers on literary standards are looking at the same thing: long-term change in 19th Century literary culture has a direction – where that culture is understood to include readers, writers, reviewers, publishers and the interactions among them. Underwood and Sellers weren’t looking for such a direction, but have (perhaps somewhat reluctantly) come to realize that that’s what they’ve stumbled upon. Jockers seems a bit puzzled by the model of influence he built (pp. 167-168); but in any event, he doesn’t recognize it as a model of directional change. That interpretation of his model is my own.

When I say “direction” what do I mean?

That’s a very tricky question. In their full paper Underwood and Sellers devote two long paragraphs (pp. 20-21) to warding off the spectre of Whig history – the horror! the horror! In the Whiggish view, history has a direction, and that direction is a progression from primitive barbarism to the wonders of (current Western) civilization. When they talk of direction, THAT’s not what Underwood and Sellers mean.

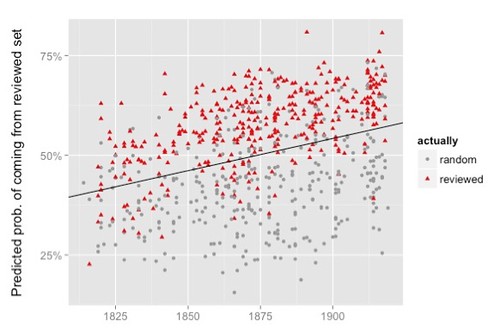

But just what DO they mean? Here’s a figure from their work:

Notice that we’re depicting time along the X-axis (horizontal), from roughly 1820 at the left to 1920 on the right. Each dot in the graph, regardless of color (red, gray) or shape (triangle, circle), represents a volume of poetry and its position on the X-axis is volume’s publication date.

But what about the Y-axis (vertical)? That’s tricky, so let us set that aside for a moment. The thing to pay attention to is the overall relation of these volumes of poetry to that axis. Notice that as we move from left to right, the volumes seem to drift upward along the Y-axis, a drift that’s easily seen in the trend line. That upward drift is the direction that Underwood and Sellers are talking about. That upward drift was not at all what they were expecting.

Drifting in Space

But what does the upward drift represent? What’s it about? It represents movement in some space, and that space represents poetic diction or language. What we see along the Y-axis is a one-dimensional reduction or projection of a space that in fact has 3200 dimensions. Now, that’s not how Underwood and Sellers characterize the Y-axis. That’s my reinterpretation of that axis. I may or may not get around to writing a post in which I explain why that’s a reasonable interpretation. Continue reading “Underwood and Sellers 2015: Cosmic Background Radiation, an Aesthetic Realm, and the Direction of 19thC Poetic Diction”