You can watch Russell Gray give three lectures about evolutionary approaches to language, cognition and culture at this year’s Nijmegen lectures. Gray covered a huge range of studies from tool use by New Caledonian Crows and crafting stone tools by hominids to quantitative work on historical linguistics and charting the evolution of political systems.

Author: Sean

Fellowship opportunity in Language Evolution, Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh are offering a Chancellor’s fellowship and are keen to attract applicants particularly in the area of language evolution. The position is a 5 year post doc that is expected to result in a permanent position. More details are available here, including Chancellor’s fellowships in other areas of linguistics.

There’s been much anxiety about opportunities for early career researchers, but the last two years have seen a bumper crop of jobs in cultural evolution, including projects in Reading, St. Andrews, Tübingen, Rome and ANU Canberra. The future’s bright!

Five Year Postdoctoral Position, Australian National University: The Wellsprings of Linguistic Diversity

This is a job advert for a computational linguist/cultural evolutionist at the Australian National University in Canberra. It’s basically the dream job for a modeller – you’ll get to help design the data that a team of field linguists collect, then be handed loads of linguistic and demographic data to model. And 5 years is a huge amount of job security for an early career researcher.

The official advert follows:

This position is being re-advertised with a new deadline of March 2nd 2014.

Applications are invited from suitably qualified scholars for a postdoctoral fellowship to work with Prof Nick Evans’ Laureate Fellowship project, ‘The Wellsprings of Linguistic Diversity’. The role of this position will be to develop appropriate computationally-based models of language change and diversification in small-scale and multilingual language communities, in close collaboration with a team of field linguists who will be gathering on-the-ground data from field sites in Aboriginal Australia, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Samoa, and small-scale communities in Australia (English) and Latin America (Spanish or Portuguese). Full details of the position and a background description of the project can be found at: http://jobs.anu.edu.au/PositionDetail.aspx?p=3715

This is a five year fixed term research position within the School of Culture, History and Language, ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, commencing June 30th, 2014.

The successful applicant will have a PhD in a relevant discipline. S/he will carry out independent and team based research as per project plan and focus on computational modelling of language evolution within the overall team, who will be collecting data and feeding that data back into the models being developed. The appointee will work under the supervision of the Laureate Project Leader and work closely with other team members and PhD students working on the project in the design and analysis of linguistic data to be gathered across a range of small-scale speech communities, since the goal of the project is to achieve a new type of interaction between detailed sociolinguistic field research on small-scale communities and computational approaches to modelling linguistic change and diversification. They will interact informally with a wide range of scholars in Linguistics and neighbouring disciplines.

The purpose of this position is to provide computational modelling expertise within the overall team, so as to (a) develop models of how micro-variation iterates over many generations to produce linguistic change (b) model the effects of multilingualism and societal scale and structure on the evolution of linguistic diversity and disparity (c) work with project members gathering linguistic and social data in a range of small-scale speech communities to design appropriate data structures for the representation and analysis of linguistic, cultural and demographic data (d) test theoretical models against the actual linguistic data collected by project members, and feed that data back into the models being developed. Ample opportunities for publication will exist, both individually and with various combinations of project members.

For further information, please contact:

Prof Nick Evans

Ph: +61 (0)2 6125 0028

Workshop: On the Emergence of Consensus and Misunderstanding: Models and Experiments

Call for participants for an interdisciplinary workshop “On the Emergence of Consensus and Misunderstanding: Models and Experiments“. The workshop will be held at La Sapienza University in Rome, Italy, 24-25 of February, 2014.

Understanding the origins and evolution of consensus and misunderstanding is one of the most stimulating areas of research in cognitive and social sciences. This challenging question touches on all aspects of cognition and social interaction, calling for creative thinking and casting fundamental issues in cognitive science in a new light.

This workshop aims to highlight issues surrounding consensus and misunderstanding by showcasing two core lines of research: theoretical modeling and experiments. Modelling is a crucial tool in the investigation of how consensus and dominant norms emerge in societies, or rather, how fragmentation and misunderstanding phenomena occur. This is relevant for the dynamics of language, opinions and other cultural traits, and the processes of individual and collective decision making. From the level of the single individual, to pairs in interaction, to populations of heterogeneous agents, formal models are ubiquitously used to make systematic observations, uncover regularities, advance hypotheses, and test their predictions. However, while such “bare-bones” models can illuminate the skeletal dynamics at work, it is becoming more and more urgent to parallel computational investigations with carefully devised social experiments. Such experiments must aim to investigate specific aspects of how individuals make decisions and how these decisions affect large-scale dynamics at the population level. Increasingly, the opportunity to run large-scale web-based experiments makes the collection of data regarding actual social behaviour more feasible.

This workshop will focus around talks and discussion featuring ongoing empirical work relevant to emergent consensus and misunderstanding, from both modeling and experimental approaches. Bringing together perspectives from psychology, physics, linguistics, and philosophy, the workshop will provide an interdisciplinary approach catered to the nature of the broad phenomena of consensus and misunderstanding.

If you are interested in presenting a poster or talk at the workshop, go to the registration page and provide a short abstract in the “Abstract” field. You will receive information regarding your presentation (i.e., poster or talk) by January 5, 2014.

Is “Huh?” a universal word?

A paper in PLOS ONE this week argues that “Huh?”, as in “What did you say?”, is a universal word with the same form and function in many languages (see here for a brief overview).

When a conversation breaks down, maybe because something wasn’t heard properly, an interlocutor can initiate conversational repair by using a range of strategies. For instance, by questioning a particular word (“whose car?”) or by using a formal response such as “Pardon?”. While the forms of these types varies across language, the strategy of signalling complete lack of understanding is accomplished in 30 languages by a word like “huh?”. The precise phonetic properties of these words in 10 languages are analysed in the paper. Here’s a video of how they all sound:

The research follows from a large-scale project at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics that collected conversational data from 10 languages, transcribed them and analysed how turn-taking and repair works in each in a Conversation Analysis framework.

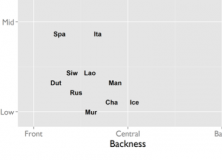

The authors argue that this is a lexical word (which is not innately constrained, like laughter), which has emerged by convergent evolution. “Huh?” is ideal for initiating repair because it’s a short, question-like word that requires minimal effort to produce and is effective at signalling a problem. The phonetic analysis shows that the word has adapted to the phonologies of the particular languages (e.g. the vowel being closer to canonical vowels in that language), but the overall similarity of the words is striking.

They don’t rule out the possibility that the word was inherited into languages from an ancestral form, but they also point out that conversational interaction is one of the primary ecologies for language evolution:

“our study points to a factor that may constrain divergence or diachronic drift: the selective pressures of specific conversational environments, which may cause convergent cultural evolution. The possibility should not be surprising. After all, words evolve in utterances in conversation, so conversational infrastructure is part of the evolutionary landscape for words. We are referring here to the sequential infrastructure that serves as the common vehicle for language use – an infrastructure that may well pre-date more complex forms of language and that seems largely independent of sometimes radical differences between individual languages’ grammars and [lexicons].”

The authors are currently extending this work to see if there are cross-cultural similarities in how the whole system of repair works.

You can read more about the project at ideophone.

Dingemanse M, Torreira F, Enfield NJ (2013) Is “Huh?” a Universal Word? Conversational Infrastructure and the Convergent Evolution of Linguistic Items. PLoS ONE 8(11): e78273. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078273 Read the paper online (open access).

Strange Tongues: Science Fiction and Language 1

This is a guest post by Joses Ho.

Science fiction has been called “the fiction of ideas”. In this series of blog posts we catalogue a (non-exhaustive) list of works in the genre that explore ideas about language and linguistics.

Science fiction (abbreviated SF amongst devotees) has been called “the fiction of ideas”. And what a pantheon of eye-glazing, heart-palpitating, and brain-melting ideas: time travel, cyborg consciousness, alien invasions. However, does SF go further than mere fictive investigation of cool concepts? Can SF be a fiction of ideas about ideas?

One such idea about ideas, familiar to anyone who paid attention in any introductory undergraduate lecture on linguistics or cognitive science, is linguistic relativity (also popularly known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis). Briefly, for the benefit of the rest of us who fell asleep in aforementioned lectures, it conjectures that the language you speak determines and shapes the way you think and the way you perceive “the universe around you” (Star Trek fans will instantly think of the Tamarian language, which can only be understood if you know the cultural references). Below I discuss 3 works that play with this idea.

1. Story of Your Life

Our first example of a SF piece that explores linguistic relativity is the novella Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang, first published in 1998, and soon to be adapted into a movie.

An alien race of Heptopods has landed on Earth, and our protagonist and narrator, Louise Banks, is a linguist contacted by the US military to learn their language and communicate with them. As the tale unfolds, Louise’s very view of reality is radically altered as she masters the written language of the Heptopods. Louise tells the reader:

…Even though I’m proficient with [written Heptapod], I know I don’t experience reality the way a heptapod does. My mind was cast in the mould of human languages, and no amount of immersion in an alien language can completely reshape it. My world-view is an amalgam of human and heptapod.

Chiang brilliantly employs an unusual narrative structure to reflect this, and we are given a glimpse into how linguistic relativity might actually work in real time.

This novella is also characteristic of Chiang’s SF work, which consists solely of short stories, written with economic prose and crisp exposition fined-tuned to deliver devastatingly satisfying endings.

2. Words and Music

Another shorter example is Words And Music by Ronald D. Ferguson. Describing an alien species known as the Utmano, the narrator tells us:

.., Utmano translation doesn’t compare well to translations among human languages. The Utmano language has a peculiar view of tense, you know, past, present, future, in its sentences — well maybe not sentences, but the complete-thought communication structure. Psychologists claim that the Utmano have a lingering, vivid, recent memory combined with a mild prescience that blends with their perception of the ‘now’. It sounds like gobbledegook, but they claim that the Utmano idea of the present spans from the middle of last week to a couple of hours from now.

The above expository paragraph is more typical of how linguistic relativity is explored in SF. While Words and Music doesn’t quite go as far as Chiang does in using the narrative structure itself to illustrate the alien mode of perception being described, Ferguson uses a novel framing device to pack quite a bit of story and exposition into a short space.

3. Embassytown

Our last selection is novel by celebrated SF writer China Miéville. Embassytown was his ninth novel and features the Ariekei, an alien race whose spoken language involved vocalizing two words simultaneously.

This is not a terribly new idea; Ferguson makes mention of this in Words and Music. In Ferguson’s story, the humans successfully apply the obvious solution (used by real-world linguists in the field as well, and mentioned in Story of Your Life) to the problem of communicating with such an alien race: use pre-recorded or synthetic speech. But Miéville won’t have that.

Synthetic speech is indiscernible to the Ariekei, because they require an actual mind to be uttering each (simultaneous) syllable. And so, the intergalatic human Ambassadors are specially-bred twins whose minds are linked, able to speak with two mouths and one mind. (If that idea doesn’t make your eyes glaze and brain melt, you are probably an Ariekei.)

These Ambassadors are the only ones who can communicate with the Ariekei, and are crucial to human-Ariekei diplomatic and trade relations. The plot gets truly interesting when a new pair of ambassadors arrives to the city of the novel’s title. These two individuals are not genetically identical, but have been selected for linkage based on their high degree of empathy. When they speak the alien language (which Miéville simply christens, a little pompously, “Language”), the effect on the Ariekei is unprecedented: they become addicted to the new Ambassador’s speech.

The rest of the novel runs along on a action-filled plot, and still manages to raise questions about mind, intelligence, and the very nature of language.

However, despite how strange the Ariekei appear, there are cases of human language use that are similar to the way their “Language” functions. Humans actually can speak two things simultaneously, using signed language and spoken language. This is called “code-blending”. Interestingly, the two words they speak and sign simultaneously can refer to different things, or are “semantically non-equivalent.”

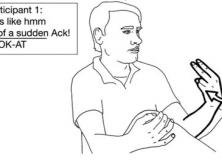

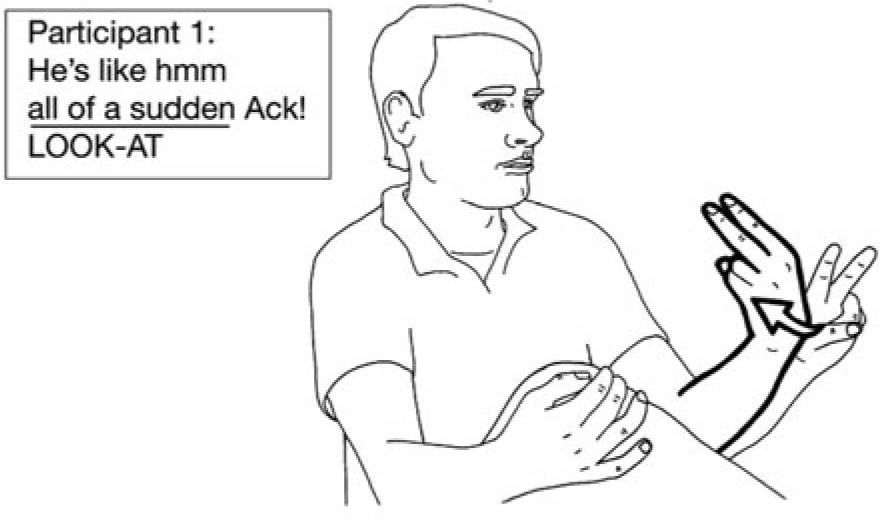

An example is given below; the capitalised text on the lower line represents the signs used (taken from Emmorey, Bornstein & Thompson (2005) and Emmorey et al., 2008).

In this picture, a man is describing a scene between the cartoon characters Sylvester the cat and Tweety the bird.

“He” refers to Sylvester who is nonchalantly watching Tweety swinging inside his bird cage on the window sill. Then all of a sudden, Tweety turns around and looks right at Sylvester and screams (“Ack!”). The sign glossed as LOOK-AT-ME is produced at the same time as the English words “all of a sudden.” [The emphasis is mine, and not in the original academic paper.]

The speaker is using both signed language and spoken language to narrate how Tweety suddenly turns to look at Sylvester sneaking up on him. So the simultaneous speech sounds of Miéville’s Ariekei might not be that far off from actual human communication.

This cross-modal flexibility in human communication may suggest that, no matter how intertwined language and thought may be, there may be no language that we truly won’t be able to understand.

Further reading

We are by no means the only ones to have noticed how linguistics is a well-explored topic in SF. There is an excellent entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction devoted to linguistics as a topic and a trope in science fiction; its exhaustive breadth (it is an encyclopedia article, after all) is remarkable, listing several source texts in a polished tone, although it omits to mention the specific pieces of fiction we have discussed above.

Dr. Maggie Browning, an associate professor in linguistics at Princeton, has compiled a bullet-point list on her website. The book recommendation site Goodreads features as well a crowdsourced list titled “Science Fiction using Languages or Linguistics as a Plot Device”. Both places are invaluable starting points for relevant primary material.

Last, but not least, there is the Alien Tongues blog, written by two graduate students in linguistics, and focussing on the links between SF and linguistics. It has several posts on the constructed languages found in much of SF.

We hope you have enjoyed this post, which we hope this will not be the last on this fascinating topic!

Joses Ho is a currently pursuing a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Oxford, and as a visiting researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. His interests also include science fiction, theology, and film. His fiction and poetry have appeared, respectively, in Nature Futures and Quarterly Literary Review Singapore. Follow him on Twitter; his handle is @jacuzzijo.

Russell Gray: The Evolution of language, culture and cognition (call for posters)

Professor Russell Gray (University of Auckland, New Zealand) will present his work on the evolution of language, culture and cognition at the annual Nijmegen Lectures in January 2014.

Professor Russell Gray (University of Auckland, New Zealand) will present his work on the evolution of language, culture and cognition at the annual Nijmegen Lectures in January 2014.

In the Nijmegen lectures series, a leading scientist in the fields of psychology or linguistics presents a three-day series of lectures and seminars. The purpose of the series is to allow broad and intensive coverage of research topics by providing extensive interaction among the invited speaker and the participants. The series is a collaborative activity of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, the Donders Institute and the Radboud University Nijmegen.

Prof. Gray will present three lectures focussing on language, culture and cognition. A number of top researchers will serve as discussants to the series, including Bart de Boer, Katie Cronin, Harald Hammarström, Ceceila Heyes, Asifa Majid and Monica Tamariz.

Call for posters

The Nijmegen Lectures will include a poster session on topics related to this year’s theme: Evolution of language, culture and cognition. We invite submissions of abstracts for posters, particularly from junior researchers, and especially studies relating to the theme of the lectures.

Please submit an abstract of no more than 300 words by email to sean.roberts@mpi.nl. Please include a title, authors, affiliations and contact email addresses (not included in the word count). The deadline is November 15th, 2013. Abstracts will be moderated by the Nijmegen lectures committee and candidates will be informed of decisions by November 29th.

The poster session will take place on January 28th from 16:30-18:00. We remind candidates that admission to the Nijmegen lectures is free, but registration is required for the afternoon discussion sessions. Please visit http://www.mpi.nl/events/nijmegen-lectures-2014 for more details. We regret that we cannot offer financial support to candidates.

Photographing language science (and language evolution)

Language scientists in Nijmegen have been showing off their artistic side, capturing their research in photography. Head over to Taal in Beeld for a look at the entries – some of them are really stunning.

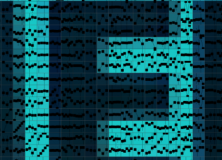

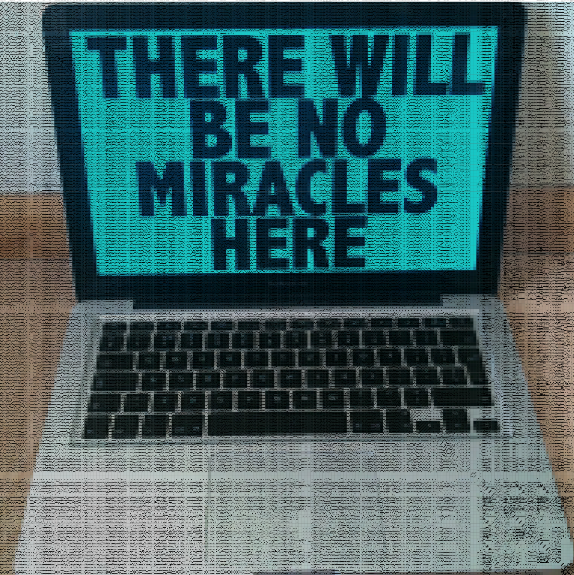

My entry was a picture of my fieldsite (my computer), made up of 36,864 graphs which show how every linguistic variable in the World Atlas of Language Structures correlates with every other variable. You can see it here. It’s inspired by my work with James Winters on spurious correlations in cultural traits.

I’m a computational linguist who looks at cross-cultural patterns in typology. With increasing amounts of data available for free, correlations are being discovered all the time between unlikely variables: Future tense and economic decisions; altitude and ejective sounds; linguistic gender and political power; linguistic diversity and traffic accidents. There’s a rush to discover interesting correlations, but actually little rigour in how the statistics are controlled.

When looking at the image, it’s tempting to try and find some correlations that look significant and imagine a causal story. However, the text on the screen (taken from artist Nathan Coley’s work “There will be no miracles here“) reminds us that, while we’d like to believe that anyone could make a chance discovery that explains how language works, we must remain rational and keep in mind the bigger picture.

You can download the full image here (22MB). And here’s the R script that made the picture.

The Taal in Beeld exhibition will be on display throughout October in the central hall of the Mariënburg Library in the center of Nijmegen.

Uncovering spurious correlations between language and culture

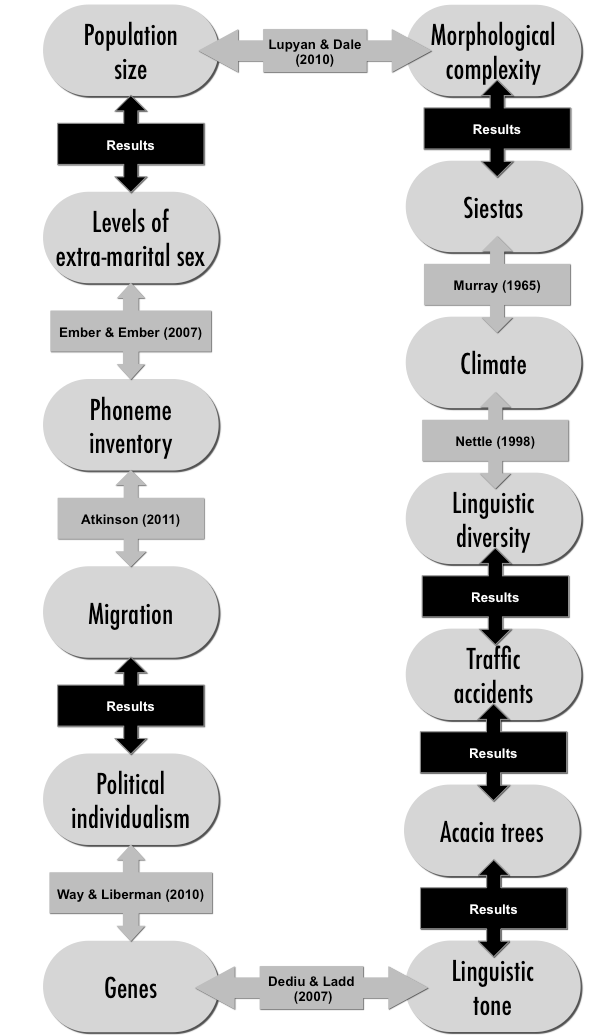

James and I have a new paper out in PLOS ONE where we demonstrate a whole host of unexpected correlations between cultural features. These include acacia trees and linguistic tone, morphology and siestas, and traffic accidents and linguistic diversity.

We hope it will be a touchstone for discussing the problems with analysing cross-cultural statistics, and a warning not to take all correlations at face value. It’s becoming increasingly important to understand these issues, both for researchers as more data becomes available, and for the general public as they read more about these kinds of study in the media (e.g. recent coverage in National Geographic, the BBC and TED). But why are the public fascinated with these findings? Here’s my guess:

People are always intrigued by stories of scientific discovery. From Mary Anning‘s discovery of a fossilised ichthyosaur when she was just 12 years old, to Fleming’s accidental production of penicilin to Newton’s apple, it’s tempting to think that anyone could trip over a major breakthrough that is out there just waiting to be found. This is perhaps why there has been so much media interest recently in studies which show surprising statistical links between cultural features such as chocolate consumption and Nobel laureates, future tense and economic decisions, linguistic gender and power or geography and phoneme inventory.

Caleb Everett, who recently discovered a link between altitude and the use of ejective sounds, describes his discovery in these terms:

Everett recalled being shocked by his discovery. “I remember stepping out from my desk and saying, ‘Okay, this is kind of crazy,'” he said. “My first question was, How had we not noticed this?”

That is, we live in an age when there is more data available than ever before, it’s more widely available and there are better tools to do analyses. Anyone with an ordinary laptop and access to the internet could make these discoveries. Indeed, we’ve uncovered many unexpected correlations at Replicated Typo. However, just as Anning’s discoveries were made as the theory of biological evolution was still developing, the ability to detect correlations in cultural features is outstripping the understanding of how to assess these findings. Early reconstructions of fossils included a lot of errors, some of which have been difficult to redress in the public’s mind. Without a good understanding of cultural evolution, similar mistakes might be made during the current race to find statistical links in our field.

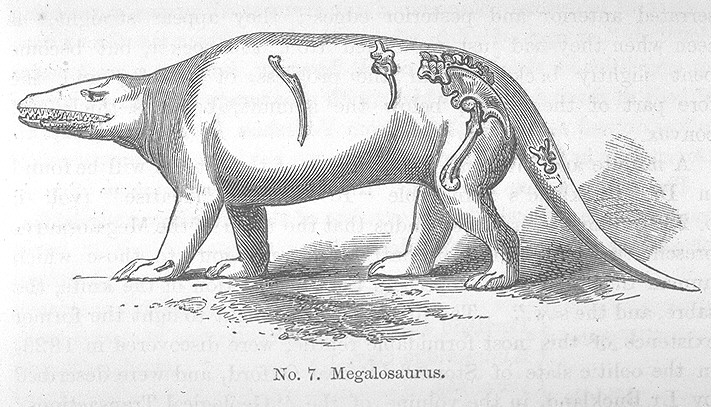

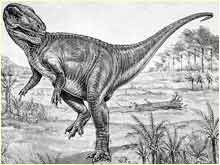

An early reconstruction of Megalosaurus by Richard Owen, based on limited evidence and theory, compared with the modern reconstruction source

Everyone knows that correlation does not imply causation, but there are other problems inherent in studies of cultural features. One problem that is often discounted in these kinds of study is the historical relationship between cultures. Cultural features tend to diffuse in bundles, inflating the apparent links between causally unrelated features. This means that it’s not a good idea to count cultures or languages as independent from each other. Here’s an example: Suppose we look at a group of highschool students and wonder whether the colour of their t-shirts correlates with the kind of food they bring for lunch. We survey 10 children, and see that 5 wear red t-shirts and eat peanut-butter sandwiches. This appears to be strong evidence for a link, but then we see that these 5 pupils come from the same family. There’s now a better explanation for the trend – the children from the same family tend to have the same choice of clothes and are given the same lunch by their parents. The same problem exists for languages. Languages in the same historical families, like English and German, tend to have inherited the same bundles of linguistic features. For this reason, it can be quite complicated to work out whether there really are causal links between cultural properties.

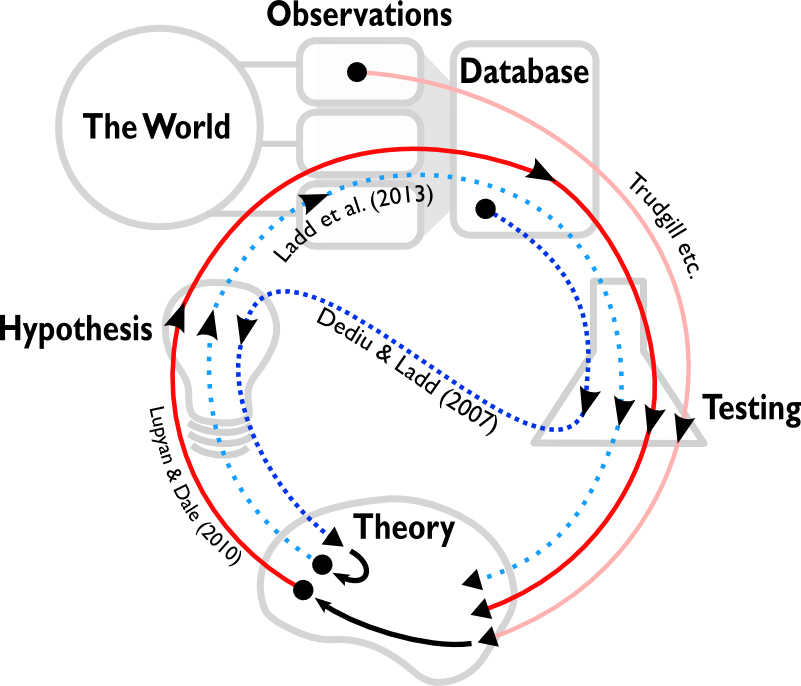

Our paper tries to demonstrate the importance of controlling for this problem by pointing out a chain of statistically significant links, some of which are unlikely to be causal. The diagram below shows the links, those marked with ‘Results’ are links that we’ve discovered and demonstrate in the paper.

For instance, linguistic diversity is correlated with the number of traffic accidents in a country, even controlling for population size, population density, GDP and latitude. While there may be hidden causes, such as state cohesion, it would be a mistake to take this as evidence that linguistic diversity caused traffic accidents.

In the paper we suggest that correlation studies should demonstrate at least two things:

- That the hypothesised correlation is stronger than correlations between similar cultural features that are not expected to be linked.

- That the hypothesised correlation is robust against controlling for cultural descent.

We discuss some methods for achieving this, and demonstrate that they can debunk the spurious correlations that we discover in the first section. Many of these methods are straightforward and can be done quickly, so there’s no excuse for avoiding them.

As well as careful statistical controls, correlation studies can also be assessed based on whether they are motivated by prior theory or not. For example, Lupyan & Dale’s (2010) demonstration of a correlation between population size and morphological complexity was motivated by a long line of research on languages in contact. However, both kinds of discovery can be useful if they are seen in the context of a wider scientific method. We argue that correlation studies should be viewed as explorations of data, and as a sort of feasibility study for further, experimental, research. For example, the chance discovery of a link between genes and tone by Dediu & Ladd was not only statistically well controlled, but was used as the inspiration for more detailed laboratory experiments, rather than being seen as proof in itself.

Coming across statistical patterns by chance has always been part of the scientific process. However, with culture, it’s much more difficult to intuitively distinguish real patterns from noise or historical influence. Correlations between unexpected features will continue to be exciting, but researchers should apply the right controls and see the studies as motivational rather than direct tests of hypotheses.

Roberts, S. & Winters, J. (2013). Linguistic Diversity and Traffic Accidents: Lessons from Statistical Studies of Cultural Traits. PLOS ONE, 8 (8) e70902 : doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070902

The SpecGram Essential Guide to Linguistics

What does a Labio-nasal sound like? What is the laziest language on earth? How can a knowledge of linguistics help make macaroni cheese? What is the tiny phoneme hypothesis? Where can you find a book that synergises all the loose ends of linguistics into a unified, transparent theory? I don’t know. In the meanwhile, try reading the Speculative Grammarian Essential Guide to Linguistics.

Many of you will know and fear the Speculative Grammarian journal, the ultimate Shibboleth in the field of languaging (and if you know what a Shibboleth is, and are proud of it, then this might be for you). Now the best cuttings have been complied into a book which takes you on a quiestionable journey right accross the field from phonetics to sociolinguistics in a quest to make linguistics look as bonkers as a real science like quantum physics.

Many of you will know and fear the Speculative Grammarian journal, the ultimate Shibboleth in the field of languaging (and if you know what a Shibboleth is, and are proud of it, then this might be for you). Now the best cuttings have been complied into a book which takes you on a quiestionable journey right accross the field from phonetics to sociolinguistics in a quest to make linguistics look as bonkers as a real science like quantum physics.

You’ll learn about the linguistic uncertainty principle (it’s impossible to simultaneously know both the synchronic state of a language and the direction of its drift). You’ll revel in the poetry of Yune O. Hūū, II. You’ll understand exactly which part of ‘no’ you don’t understand. You’ll wonder about granular phonology. In fact, you’ll wonder about a lot of things, like how this got published. It even includes the finding that started the whole spurious correlation saga, the role of the Acacia tree in language evolution.

Complete with a choose-your-own-career-in-linguistics adventure game (German-sign-language-shaped dice not included), this is the ultimate gift for the budding language student, the jaded academic or the holistic forensic linguist. And just in time for Christmas.

You can buy the book at the SpecGram website.

Dubious praise:

“Ever wonder why Vikings torched scriptoria? This kind of thing.”

—E. V. Gordon

“Funnier than any other book I’ve read in the entire 20th Century!”

—Rasmus Rask

“Contains more than 100 basic words.”

—Morris Swadesh

“Same reference as linguistics; different sense.”

—Gottlob Frege

“Most of the changes I would make are, of course, to remove commas.”

—An Anonymous Proofreader

“This book is so chock full of borrowings and analogy that it is utterly unsuited to any sort of scholarly discourse.”

—Neogrammarian Quarterly

“Two uvulas down, way down!”

—Sapir and Bloomfield, At the Bookstore