A new paper in the journal ‘Emotion’ has presented research which has implications for the evolution of language, emotion and for theories of linguistic relativity. The paper, entitled ‘Categorical Perception of Emotional Facial Expressions Does Not Require Lexical Categories’, looks at whether our perception of other people’s emotions depend on the language we speak or if it is universal. The results come from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics and Evolutionary Anthropology.

Human’s facial expressions are perceived categorically and this has lead to hypotheses that this is caused by linguistic mechanisms.

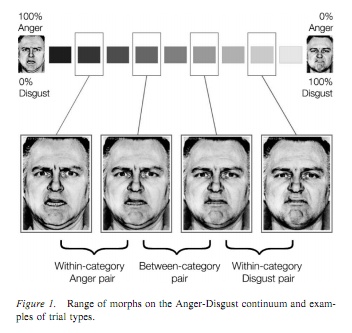

The paper presents a study which compared German speakers to native speakers of Yucatec Maya, which is a language which has no labels which distinguish disgust from anger. This was backed up by a free naming task in which speakers of German, but not Yucatec Maya, made lexical distinctions between disgust and anger.

The study comprised of a match-to-sample task of facial expressions, and both speakers of German and Yucatec Maya perceived emotional facial expressions of disgust and anger, and other emotions, categorically. This effect was shown to be just as significant across the language groups, as well as across emotion continua (see figure 1.) regardless of lexical distinctions.

The results show that the perception of emotional signals is not the result of linguistic mechanisms which create different lexical labels but instead shows evidence that emotions are subject to their own biologically evolved mechanisms. Sorry Whorfians!

References

Sauter DA, Leguen O, & Haun DB (2011). Categorical perception of emotional facial expressions does not require lexical categories. Emotion (Washington, D.C.) PMID: 22004379