I’ve collected some recent posts (from New Savanna) on patterns into a working paper. It’s online at SSRN. Here’s the abstract and the introduction.

Abstract: Literary critics seek patterns, whether patterns in individual texts or patterns in large collections of texts. Valid patterns are taken as indices of causal mechanisms of one sort or another. Most abstractly, a pattern emerges or is enacted as some machine makes its way in an environment. An ecological niche is a pattern “traced” by an organism in its environment. Literary texts are themselves patterns traced by writers (and readers) through their life worlds. Patterns are frequently described through visualizations. The concept of pattern thus dissolves the apparent conflict between quantification and meaning, for quantification is but a means to describing a pattern. It is up to the critic to determine whether or not a pattern is meaningful by identifying the mechanism that produced the pattern. Examples from Shakespeare and Joseph Conrad.

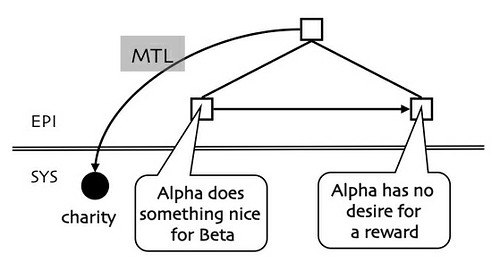

Introduction: Patterns and Descriptions There is a sense, of course, in which I’ve been aware of and have been perceiving and thinking about patterns all my life. They are ubiquitous after all. But it wasn’t until I began studying cognitive science with the late David Hays that “pattern” became a term of art. Hays and his students were developing a network model of cognitive structure – such works became common in the 1970s. Such networks admit of two general kinds of computational process, path tracing and pattern recognition. Path tracing is computationally easy, while the pattern recognition is not. Human beings, however, are very good at perceiving and recognizing patterns.

What put the idea before me, though, as something demanding specific thought, are remarks Franco Moretti made in coming to grips with his work on the network analysis of plot structure. In Network Theory, Plot Analysis (Literary Lab Pamphlet 2, 2011, p. 11) he noted that he “did not need network theory; but I probably needed networks…. What I took from network theory were less concepts than visualization.” We then examine the visualizations to determine whether or not they indicate patterns that are worth further exploration. Continue reading “Beyond Quantification: Digital Criticism and the Search for Patterns”