And he more or less knows it; but he wants to have his cake and eat it too. It’s a little late in the game to be learning new tricks.

I don’t know just when people started casually talking about the brain as a computer and the mind as software, but it’s been going on for a long time. But it’s one thing to use such language in casual conversation. It’s something else to take it as a serious way of investigating mind and brain. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, when computers and digital computing were still new and the territory – both computers and the brain – relatively unexplored, one could reasonably proceed on the assumption that brains are digital computers. But an opposed assumption – that brains cannot possibly be computers – was also plausible.

The second assumption strikes me as being beside the point for those of us who find computational ideas essential to thinking about the mind, for we can proceed without the somewhat stronger assumption that the mind/brain is just a digital computer. It seems to me that the sell-by date on that one is now past.

The major problem is that living neural tissue is quite different from silicon and metal. Silicon and metal passively take on the impress of purposes and processes humans program into them. Neural tissue is a bit trickier. As for Dennett, no one championed the computational mind more vigorously than he did, but now he’s trying to rethink his views, and that’s interesting to watch.

The Living Brain

In 2014 Tecumseh Fitch published an article in which he laid out a computational framework for “cognitive biology” [1]. In that article he pointed out why the software/hardware distinction doesn’t really work for brains (p. 314):

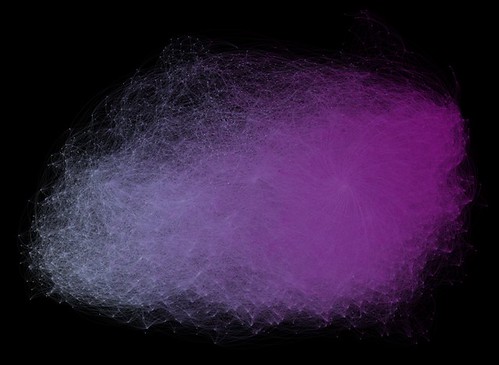

Neurons are living cells – complex self-modifying arrangements of living matter – while silicon transistors are etched and fixed. This means that applying the “software/hardware” distinction to the nervous system is misleading. The fact that neurons change their form, and that such change is at the heart of learning and plasticity, makes the term “neural hardware” particularly inappropriate. The mind is not a program running on the hardware of the brain. The mind is constituted by the ever-changing living tissue of the brain, made up of a class of complex cells, each one different in ways that matter, and that are specialized to process information.

Yes, though I’m just a little antsy about that last phrase – “specialized to process information” – as it suggests that these cells “process” information in the way that clerks process paperwork: moving it around, stamping it, denying it, approving it, amending it, and so forth. But we’ll leave that alone.

One consequence of the fact that the nervous system is made of living tissue is that it is very difficult to undo what has been learned into the detailed micro-structure of this tissue. It’s easy to wipe a hunk of code or data from a digital computer without damaging the hardware, but it’s almost impossible to do the something like that with a mind/brain. How do you remove a person’s knowledge of Chinese history, or their ability to speak Basque, and nothing else, and do so without physical harm? It’s impossible. Continue reading “Dennet’s WRONG: the Mind is NOT Software for the Brain”