That’s the title of my latest working paper. You can download it here: https://www.academia.edu/41095277/Divergence_and_Reticulation_in_Cultural_Evolution_Some_draft_text_for_an_article_in_progress.

And you can participate in a discussion of it here: https://www.academia.edu/s/9b97738023.

Abstract, Contents, and introductory material below.

* * * * *

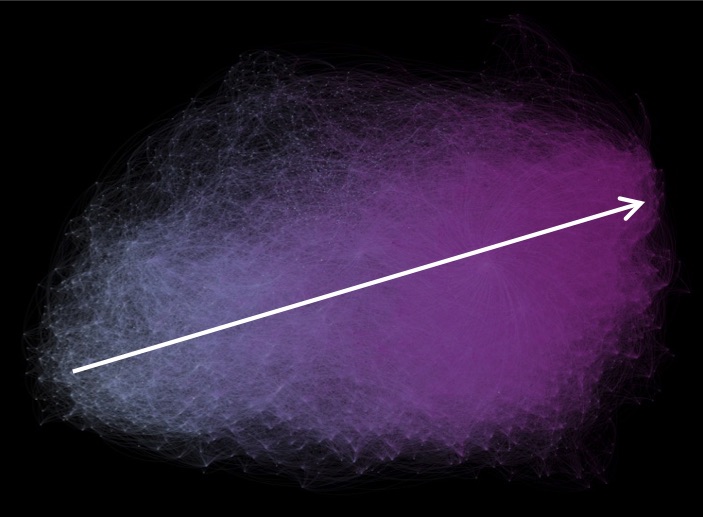

Abstract: In a recent review of articles in computational criticism Franco Moretti and Oleg Sobchuk bring up the issue of tree-like (dendriform) vs. reticular phylogenies in biology and pose the question for the form taken by the evolution of cultural objects: How is cultural information transmitted, vertically (leading to trees) or horizontally (yielding webs)? Dendriform phylogenies are particularly interesting because one can infer the phylogenetic history of an ensemble of species by examining the current state. The horizontal transmission of information in webs obscures any historical signal. I examine a few cultural examples in some detail, including jazz styles and natural language, and then take up the 3300 node graph Matthew Jockers (Macroanalysis 2013) used to depict similarity relationships between 3300 19th century Anglophone novels. The graph depicts a web-like mesh of texts but, uncharacteristically of such patterns, also exhibits a strong historical signal. (Just how that is possible is the subject of another draft.)

Contents

What’s Up? 1

The need for theory: Cultural evolution 2

Trees, Nets, and Inheritance in Biology 4

Divergence and reticulation in culture 7

Jockers’ Graph, a reticulate network 18 Appendix: A quick guide to cultural evolution 22

What’s Up?

In the past year we have had two reviews of recent work in computational criticism:

Nan Z. Da, The Computational Case against Computational Literary Studies, Critical Inquiry 45, Spring 2019, 601-639.

Franco Moretti and Oleg Sobchuk, Hidden in Plain Sight: Data Visualization in the Humanities, New Left Review 118, July August 2019, 86-119.

Though both are critical of that work, they are quite different in tone and intent. Da is broadly dismissive and sees little value in it. Moretti and Sobchuk see considerable value in the work, but are disappointed that it is largely empirical in character, failing to articulate a theoretical superstructure that deepens our understanding of literary history.

I’ve been working on a critique of those papers which seems to have expanded into a primer on thinking about literary culture as an evolutionary phenomenon. I’m currently imaging that the final article will have five parts:

- Genealogy in literary history

- Unidirectional trends in cultural evolution

- Jockers’ Graph: Direction in the 19th century Anglophone novel

- Expressive culture as a force in history

- A quick guide to cultural evolution for humanists

I have already posted draft material for the second part of the article, which centers on a graph from Matthew Jockers’ Macroanalysis (2013) [1].

That graph was my central concern from the beginning. It is the most interesting conceptual object I’ve seen in computational criticism, but it is easily misunderestimated and glossed over – as far as I know Da’s understandable but unfortunate dismissal is the only treatment of it in the referred literature. The problem, it seems to me, is that a proper appreciation of it requires a conceptual framework that doesn’t exist in the literature. My objective, then, is to begin assembling such a framework.

Moretti and Sobchuk didn’t mention it at all as their review was confined to journal articles. But it merits consideration in a framework that did establish in their review, if only barely. The invoke a distinction from evolutionary biology, that between tree-like (dendriform) phylogenies and free-form or web-like phylogenies, and suggest that it is important for understanding the relationship between literary for and history (pp. 108 ff.). Jockers graph is web-like network of texts but it exhibits an important feature of dendriform phylogenies, it displays a strong temporal signal. Thus a discussion of issues raised by Moretti and Sobchuk is a good way to begin constructing the missing conceptual framework.

This document consists of draft material for the discussion, the first part of the planned article, and the fifth part. The fifth part, the appendix is straight forward, and I have included it the end of this document. Once I have discussed the issue of dendriform vs. web-like relationships I introduce Jockers’s graph.

In the second part of the article, unidirectional trends in cultural evolution, I plan to say a few words about time and directionality. I will then take up a number of the examples Moretti and Sobchuk review in their article. While they don’t frame them as evidence for unidirectional trends, that is what they are. From my point of view that’s the most interesting and important aspect of their review, they gather those articles into one place. I will be placing those articles in the context of other work showing unidirectional trends.

I don’t yet know whether I’ll post draft materials on the second and fourth sections before drafting the whole article.

The need for theory: Cultural evolution

Now let us turn to Moretti and Sobchuk. Here is their penultimate paragraph (112-113):

Tree-like, linear, reticulate . . . why should we even care about the shape of cultural history? We should, because that shape is implicitly a hypothesis about the forces that operate within history; the tentative, intuitive beginning of a theoretical framework. ‘Theories are, even more than laboratory instruments, the essential tools of the scientist’s trade’, wrote Thomas Kuhn over a half century ago; too bad we didn’t heed his advice. Although the crass anti-intellectualism of Wired—‘correlation is enough’, ‘the scientific method is obsolete’—has fortunately remained an exception, what seems to have happened is that, as the amount of quantitative evidence at our disposal was increasing, our attempts at in-depth explanations were losing their strength. Disclaimers, postponements, ad hoc reactions, false modesty, leaving inferences ‘for another day’ . . . such have been, far too often, our inconclusive conclusions.

Ah, “the forces that operate within history”, that’s what we’re after, no? And we’re not going to get there without theory, yes?

I believe that that theory will be about culture as an evolutionary phenomenon. It is clear that both Moretti and Sobchuk believe that as well, but they do not introduce or frame their essay that way. They introduce it as a methodological inquiry into the use of visualization. It is only as the essay unfolds that evolution emerges as an ideational engine parallel to if not quite driving their interest in visualization.

Accordingly it is necessary to make some preliminary remarks about cultural evolution. Work in cultural evolution has blossomed in the last quarter century but:

While humanities and social science scholars are interested in complex phenomena—often involving the interaction between behaviour rich in semantic information, networks of social interactions, material artefacts and persisting institutions—many prominent cultural evolutionary models focus on the evolution of a few select cultural traits, or traits that vary along a single dimension […]. Moreover, when such models do build in more traits, these typically are taken to evolve independently of one another […]. Within cultural evolutionary theory, this strategy holds that the dynamics and structure of cultural evolutionary phenomena can be extrapolated from models that represent a small number of cultural traits interacting in independent (or non-epistatic) processes. This kind of strategy licences the modelling of simple trait systems, either with an eye to describing the kinematics of those simple systems, or to illuminate the evolution and operation of mechanisms underpinning their transmission […]. [2]

Hence, if students of literature want to think about culture as a phenomenon of evolutionary processes, we will not find suitable models and methods in existing work on cultural evolution. Though we certainly need to be aware of and conversant with that work, we are going to have to construct models and methods suitable to our material. That is the primary objective of this essay. To that end, then, I will be introducing a several of examples of work on cultural evolution in other domains.

Biologists, of course, has been developing evolutionary theory over the last half century. While they agree on basic issues, many details are still under contention. When we, then, as students of literary culture set out to adapt evolutionary theory to the analysis of literary phenomena, just what do we take from biological thinking and how do we do it? Various approaches exist in the general cultural literature, but this is hardly the place to sort through them – though I have prepared a brief appendix with pointers into those discussions. What Moretti and Sobchuk seem to have taken over is the distinction between tree-like lineages and more chaotic, network-like lineages. So that’s where I will start.

Where I am going, though, is toward an argument which says that that distinction is a reflection of the mechanisms that underlie the evolutionary process and it is to those mechanisms that we must look in adapting evolutionary theory to the study of human culture. Cultural evolution unfolds though collectivities of human minds, and they give cultural evolution a different texture, if you will, and different large scale patterns.

References

[1] On the direction of literary history: How should we interpret that 3300 node graph in Macroanalysis, Version 2, https://www.academia.edu/40550795/On_the_direction_of_literary_history_How_should_we_interpret_that_3300_node_graph_in_Macroanalysis_Version_2.

[2] Buskell, A., Enquist, M. & Jansson, F. A systems approach to cultural evolution. Palgrave Commun 5, 131 (2019) pp. 4-5, doi:10.1057/s41599-019-0343-5 https://rdcu.be/bVNtP.