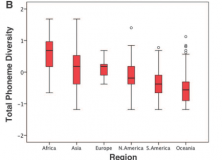

It’s been well over a year since I first wrote about the relationship between phoneme inventory size and demography (see here and here). Since then, I have completed a thesis examining this relationship further, especially in the context of the relative roles of demography and tradeoffs between other linguistic subsystems (namely, a language’s lexicon and its morphological complexity). Outside my own bubble, the topic has exploded in popularity, culminating in the publication of Quentin Atkinson’s paper, Phonemic diversity supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa. It really hit home how big the topic was when I saw that the New York Times had picked up on the article. For me, this was a double-edged sword: obviously, I saw myself as the phoneme-guy over at Replicated Typo, so having someone else take this niche topic and make it popular dented my ego somewhat, but it was also a positive development in that the idea was now going to get the attention it deserved…

… Well, it sort of did and didn’t. Atkinson raised two major theoretical points in his paper. The first, and the one I’m interested in, made the link between phoneme inventory sizes, mechanisms of cultural transmission and the underlying demographic processes supporting these changes. Sadly, it was Atkinson’s second idea – that we could develop a serial founder effect model from Africa based on the phoneme inventory size – where most of the attention fell. In a methodological sense, I admired Atkinson’s approach to testing this second hypothesis, but I did feel he jumped the gun somewhat: I think more work was needed on the cultural transmission model before testing for serial founder effects. Indeed, that we haven’t developed an initial model linking the relationship between phoneme inventory size and demography, may yet prove to be Atkinson’s downfall: we should be testing multiple explanatory models (Bayesian MCMC comparison, perhaps?) rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach.

Continue reading “The Great Mystery of the Vanishing Phonemes”