Last year Altmann, Pierrehumbert & Motter (henceforth, APM) released a great paper in PLoS One: Niche as a determinant of word fate in online groups. Having referenced the paper extensively in my non-bloggy academic world, I thought it was about time I mentioned it on a Replicated Typo. Below is the abstract:

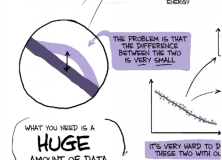

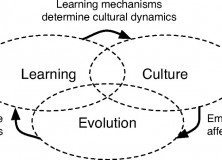

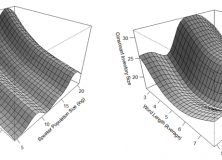

Patterns of word use both reflect and influence a myriad of human activities and interactions. Like other entities that are reproduced and evolve, words rise or decline depending upon a complex interplay between their intrinsic properties and the environments in which they function. Using Internet discussion communities as model systems, we define the concept of a word niche as the relationship between the word and the characteristic features of the environments in which it is used. We develop a method to quantify two important aspects of the word niche: the range of individuals using the word and the range of topics it is used to discuss. Controlling for word frequency, we show that these aspects of the word niche are strong determinants of changes in word frequency. Previous studies have already indicated that word frequency itself is a correlate of word success at historical time scales. Our analysis of changes in word frequencies over time reveals that the relative sizes of word niches are far more important than word frequencies in the dynamics of the entire vocabulary at shorter time scales, as the language adapts to new concepts and social groupings. We also distinguish endogenous versus exogenous factors as additional contributors to the fates of words, and demonstrate the force of this distinction in the rise of novel words. Our results indicate that short-term nonstationarity in word statistics is strongly driven by individual proclivities, including inclinations to provide novel information and to project a distinctive social identity.